Then came Peter to him, and said, Lord, how oft shall my brother sin against me, and I forgive him? till seven times? Jesus saith unto him, I say not unto thee, Until seven times: but, Until seventy times seven (St. Matthew 18:21-22).

The stakes of this 2,000 year old conversation between St. Peter and his Lord are terribly important to us. Throughout chapter 18, the Savior of the world is establishing how His church (His organization of peace between God and Man) will operate in a still fallen world. He tells the new covenant people to humbly depend upon God as if we were children depending on our fathers, to avoid sin like its cancer, to seek out the lost, to bind ourselves to the rehabilitative discipline our church and her ministers prescribe, and finally, as we hear today, we are told to assassinate our pride: to forgive our enemies as we look down at them from our crosses—ignoring the blood and the shame.

Of course, none of these commands makes any sense unless we trust in the justice of God above all else. If we still ultimately hope in our own strength or cleverness or beauty to get us through our tomorrows, even as day by day we are cruelly robbed of these strengths, if therein lies our hope and comfort then the commands of the God/Man who tells us the human project has failed, and He is here to save it, will inevitably fall on deaf ears. And, quite frankly, I understand this attitude in the 21st century West. Technology and material abundance have brought us closer than ever to being the little gods Satan convinced our first parents to try and become. If a 1st century Roman peasant saw me drive up in a car, a symphony playing on my phone, while a voice from space directed me where to go, he would think he was meeting a god, but, of course, he would be meeting a god who bleeds, a god who forgets to pick up milk when his wife asks him to, a god who stubs his toe in the dark, a god who hurts himself and others because he is deeply wounded by a broken human nature which leads all men to madly war against the true and only God and the love and justice only Christ can make real.

Here we encounter one of the tremendous and beautiful mysteries of this true God becoming man, for it is not enough for God to simply tell us what love and justice look like; no, God becomes one of us so that we can never again say love and justice are impossible. Love and justice breathed among us; love and justice lived even after we nailed Him to a tree; love and justice had a conversation with St. Peter. And, blessedly, we are allowed to sit and learn along with the far too confident apostle and learn we must if we have any chance of becoming truly human. No pressure. Although, perhaps the pressure is left off us a bit when we recognize how just incredibly wrong Peter is when he attempts to take the teachings of Jesus and apply them to his own life. He stands before the God/Man whose destiny it is to be the instrument of forgiveness for an innumerable host of people, he stands before the God who has been wronged by our human rebellion for thousands of years, he stands there and suggests that the most he can possibly be expected to forgive his brother is seven times. This statement is like boasting to a purple heart wearing amputee about surviving a particularly stingy paper cut. To be fair to the apostle, he was doubling and adding one to the traditional rabbinical teaching which looked at the Book of Amos and extrapolated that you only had to forgive people three times, and then you could drop the hammer. As in so much of the rabbinical analysis, this conclusion is eminently logical, perfectly reasonable, and a death sentence for humanity. Whatever little forgiveness system we’ve invented is almost certainly much less reasonable, not nearly as logical, and a death sentence for us.

What is Jesus’ answer to St. Peter’s system, and, of course, our little systems too? Well, He takes the Hebrew number for completeness (seven) and puts it with another seven as a poetic way of saying ‘infinity.’ Jesus looks at St. Peter, He looks at us, and sees whatever amount of forgiveness we think is appropriate and raises us to infinity. It is a shocking pronouncement. But why speak in this poetic manner? Why not just say, ‘You must always forgive?’ Well, just as the Gospel is not our story, the forgiveness we offer in the name of Jesus Christ is not about us. By forgiving all those who have hurt us, we are connecting ourselves into the God/Man’s reclamation of human nature from the dark rebellion of our forefathers. As we hear on the lips of the evil and terrible Lamech all the way back in Genesis 4, ‘…hear my voice; you wives of Lamech, listen to what I say: I have killed a man for wounding me, a young man for striking me. If Cain’s revenge is sevenfold, then Lamech’s is seventy-sevenfold’ (Genesis 4:23-24). Here is the battle cry of fallen man: ‘I am the one who determines what is the just punishment for wronging me; I will judge and punish because that is the only way in which my pain can be healed.’ Christ’s command today is the courageous and terrible antidote to Lamech’s poisonous revenge. It is the reversal of the pain he wanted to cause; it is the taking of that pain upon ourselves: the offering up of that pain to the God who knows what it means to be a sacrifice for the forgiveness of the world. Despite all his murderous posturing, Lamech was a coward because he couldn’t take the pain which inevitably follows true, sacrificial forgiveness; Jesus is our Savior because He can.

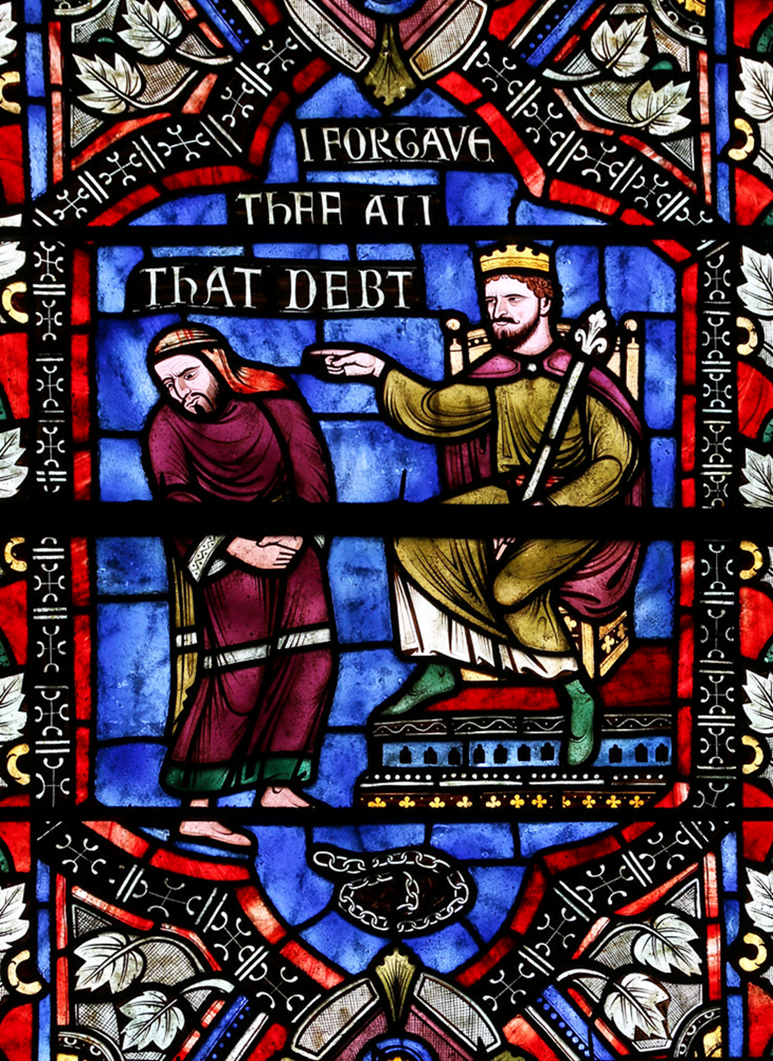

To illustrate the enormity of the cosmic, creation healing forgiveness we are being commanded to join, Jesus presents a parable. If we grasp one thing from this parable, let it be this: through the death of Christ, we have been forgiven a debt of incalculable size. The figure represented in the Greek is the highest number capable of being produced with 2 words; it’s the equivalent of the king in the parable forgiving an individual American the 35 trillion dollars worth of debt our nation owes its many creditors. There’s probably a whole sermon in which we could meditate on how it’s likely impossible for a country willing to leave that much debt to its future generations to be serious about the debt of sin, but it suffices to say that the two are not unrelated. In the parable (as in life) the servant has nothing to give the king, nothing which could possibly equal the sum he owes. The fair thing to do would be for the king to justly punish this man, to torture the debt out of his flesh, to take his life and the lives of his wife and children. We must hold this massive debt in our minds to understand the enormity of what the king is doing here, but also to eliminate any notion that the servant’s act of surrender somehow merits the forgiveness he receives. Falling on his knees and begging for forgiveness is the only reasonable action a human can take when faced with the true enormity of our failed rebellion’s cost: broken hearts, dead children, misery, sadness, pain. The mercy we receive is not measured by how sorry we are or how much we cry or some other means through which we can twist this story into being about us; no, mercy is unmerited because we have nothing except our surrender to offer. It is a unique mark of the God whose name is Love that this surrender is enough; it is a revelation of God’s strength that He can look upon a miserable debtor and say, ‘Thy sins are forgiven thee.’

But, a reasonable question to ask here is: What about the money? Does the king just magically forgive the ‘gazillion’ dollars the servant owes? No, that’s not how debt works. Someone must pay. Just as someone must pay our sin debt or else good and evil are nothing more than illusions, and it is here where we start to understand the gravity of what Jesus is saying to Peter, to the other apostles, and to us. When Christ commands His church to adopt a radical, death-to-self kind of forgiveness, He does so knowing full well what the cost of forgiveness truly is. He knows the price of our forgiveness will be His unjust murder at the hands of the very people He came to save. There is nothing fair about Calvary: there is only the God/Man paying our unpayable debt with His blood and pain and life. There is nothing fair about us forgiving our brother or sister or enemy: there is only our recognition of what God has done for us and what we must now do to honor the God who has made us free.

And so, when we are faced with an opportunity to forgive and live in love with another God forgiven debtor, we should not even think about what the repentant person has done to us, we should only be able to see what God has done for us; we should only be able to see the Cross and our Lord—bleeding and forgiving us from His victorious perch. Consequently, there is no ‘forgive but not forget’ for the Christian: we forgive as we have been forgiven—if we don’t believe that we should just stop saying the Lord’s Prayer—we forgive from the new human hearts Christ’s sacrifice has placed in our chests, or we should just accept we carry the stony, unfeeling hearts of the walking dead. Let it never be so. Let us embrace God’s victory over death through the resurrection of Jesus Christ; let us embrace God’s victory over shame and revenge in His freely given unmerited forgiveness; let us know that the only way to real forgiveness is through knowing we are the forgiven