For if the inheritance be of the law, it is no more of promise: but God gave it to Abraham by promise (Galatians 3:18).

At the heart of today’s epistle is an extended argument regarding the destiny of the world. It may not seem that way to us as we wade through one of Galatian’s chapter-long discussions of law and covenants, circumcision and inheritance, but nothing less than life and death, divine wrath and glorious redemption are the topics before us today—culminating with all the intense, personal and cosmic ramifications real answers from God cannot help but provide to us.

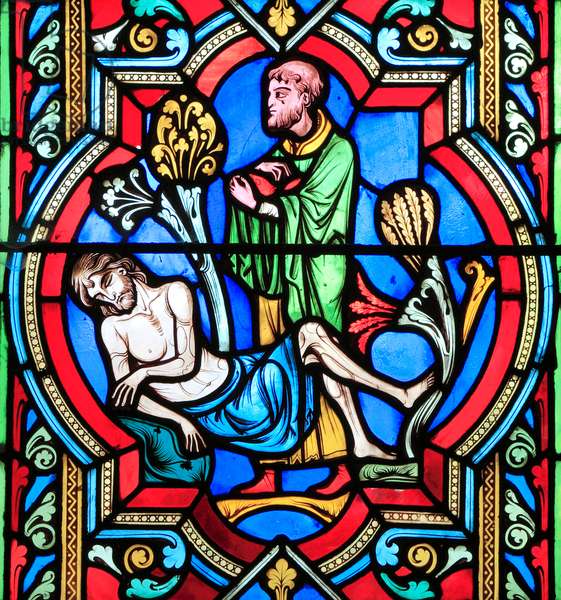

I said this letter is full of arguments, sometimes quite heated ones, but the most pressing one regards what it means to be in the family of God once the promised messiah has come to gather His people into His kingdom. The immediate problem the early church faced was what to do with all the Gentiles, reborn by water and the Holy Spirit, who had now been grafted into the vine of Christ. These men and women had been, as St. Paul describes, ‘…separated from Christ, alienated from the commonwealth of Israel and strangers to the covenants of promise, having no hope and without God in the world’ (Ephesians 2:12), but were now ‘brought near by the blood of Christ’ (Ephesians 2:13). Paul himself, hand picked by God on the Damascus road to reach the lost Gentile nations, had seen the mighty hand of God move the hearts of men and bring them into Christ’s service, and not just the lost sheep of the house of Israel, but Gentile ‘dogs’ (as they were commonly known in Jewish conversation) were being given seats at the table for the Lord’s Supper and for the future wedding feast of the Lamb.

Paul could see God on the march and that all of these human shaped victories speak to the erupting fulfillment of ancient prophecy. As Isaiah writes, ‘Arise, shine, for your light has come, and the glory of the Lord has risen upon you. For behold, darkness shall cover the earth, and thick darkness the peoples; but the Lord will arise upon you, and his glory will be seen upon you. And Gentiles shall come to thy light, and kings to the brightness of thy rising’ (Isaiah 60:1-3). The ‘light’ had come in Christ, and because the darkness of death was not able to overcome Him, the Gentiles were flocking to the overwhelming brightness of resurrection joy. It is important for us never to forget how blessed we are to be able to share this everlasting joy with one another. Nothing about us matters at all if we are not brought near to God by the blood of Christ; this was true of the first jubilant Gentiles, and it should be manifestly true of us.

But, as we see today, joy is not everything. Give me joyful over jaded every day of the week, but joy is not the only part of the Christian life. How often do the apostles instruct us to be careful and wary of the dark forces which swirl all around us? Whether it’s Paul telling us to put on the armor of light or St. Peter advising us to be on the lookout for the Devil as if we were on watch for a man-eating lion, our many enemies—both natural and supernatural—seek to glory in our flesh and tears and pain. The worst of these foes believe they are doing what’s best for us; they believe they are on the side of the angels but instead find themselves in the service of those fallen messengers of God who repeat again and again, ‘I will not serve.’

St. Paul’s targeted enemies, usually called Judaizers, believed the only way to be part of the people of God was to gain the favor of God through submission to every part of the ritual law—which included, among many other things, the circumcision of male converts. In these Judaizers’ minds, new life and resurrection joy were all well and good, but it was the following of the law which truly made one a member of God’s holy, chosen people. As with almost all heresies, the problem comes not in the object these men promoted but in their taking of a real truth (the goodness of the law) and using this true and good thing as a weapon against God and His sovereignty. As evidenced throughout church history, heresies operate by promoting human works or some idol’s works over the saving work of Christ on the Cross. St. Paul, on the other hand, commands us to see the truth: nothing, not even the divine law given to Moses, can save us from the sinful nature we inherited from our parents and sadly participate in whenever we choose death over life by sinning ourselves.

But, none of this harsh but fair assessment of humanity really makes sense to us unless we are familiar with the actual arguments St. Paul makes today. The working assumption of the apostle is that when either Jew or Gentile enter the church they must desire to know all they can about the saving works of God in history. No longer would a Gentile see the campaigns of the Caesars as the ultimate march toward earthly peace; no longer would the Jew look to the Maccabees as the historical template for a holy future; no, it is the active, covenantal work of God in history which provides mankind’s only hope and comfort, and in the age of the church, we glory in God’s revelation to us that the Christ who saved us and promises to return is the same mighty Seed promised to Adam and Eve in Genesis, the same Seed promised to Abraham in the covenant of promise, the same Seed harvested in the first resurrection we all will soon experience.

St. Paul then is driving us to observe the whole counsel of God (the entirety of the Scriptures) as the story of the Trinity’s world-saving mission—now fully inaugurated in the death and resurrection of Christ and the coming of the Holy Spirit. The Mosaic law, while important for showing us just how much we need a Savior, is but one part of this enormous time-spanning saga of mankind’s divinely ordered salvation. The less we know about this actual historical drama, the more we will fill in our own idols and myths to take its place: We may not demand that all men be circumcised, but we might demand that all men think about this week’s political fights in the same way we do, or we might demand that a Christian brother unquestioningly mirror our extra-scriptural cultural beliefs, or we might adopt whatever demonic cause for disunity we can use to attack Christ’s church so as to better pretend we are her master.

And so, St. Paul does not refute the Judaizers by telling them to ignore the Old Testament because now we’re all New Testament Christians; no, he goes to the promises of the Old Testament to reveal how they are being fulfilled in the New Testament, for without the promises, we cannot know the fulfillment; without the promises, we cannot know where we are going or why we are going there. In short, if we ignore the promises of the Old Testament we find ourselves in terrible danger of trying to create our own fulfillment, and there is nothing but darkness and death down that well-worn path.

But why then would any person alive ignore the true story of God’s world saving love of His creation? Why would we trust any other history more than the history of the people to whom God Himself made a covenant? Well, we seek peace in other histories for the same reason humanity always chooses law over grace in its failed religious endeavors: we want to be God, and so we want control—even, nay especially, if that control consists of a long series of laws or rules we can try to follow to somehow put God in our debt. Whether our laws of living are constructed by God Himself or some philosopher or politician to whom we are unwittingly captive, there is absolutely no hope of salvation in our individual performance of them. How could there be? How could the dead and dying things of this world make us alive?

Imagine for a moment all of the rules and laws and sayings and folk wisdoms and half-truths being screamed at us every hour of every day throughout every moment of history, all of it melting together into the constant, ignorant howl of the damned. This is our life, particularly in the age of the internet, and it can be so very hard to focus when we are in the midst of it. The only thing capable of silencing this deafening roar is the cry of the Son of God, ‘It is finished.’ Calvary is where the foolishness of all our merits and self-righteousness is to be forever found—shown forth and received again and again in the Lord’s Supper we are privileged to celebrate today. We bring our repentance to the table, and Christ gives us His righteousness—a righteousness which can only come from the one man who actually followed the whole law: The only man to die and rise so that we could share in the unending spoils of His victory.

And so, we begin to see why men left to their own devices will always choose law over the Cross. They choose rules over sacrificial love because the Cross demands so much more than a checklist ever could. The Cross demands from us our hearts and souls and minds, not so that we might save ourselves, but in the ultimate recognition that we have been saved by another, and He is now the perfect master of our lives.

To know this truth is to know we are free; free to live not as captives of sin or beasts with cell-phones but as redeemed men and women of the new heaven and new earth—heirs according to promise, sons and daughters of God through faith. And in that freedom lies the great adventure of a life made new in Christ. A life lived not in fear but rather in wonder and awe at the glory shining through the good works God put us on earth to fulfill. The glory of all God’s promises kept through the breath and blood and bones of a chosen people.