Now from the sixth hour there was darkness over all the land (St. Matthew 27:45).

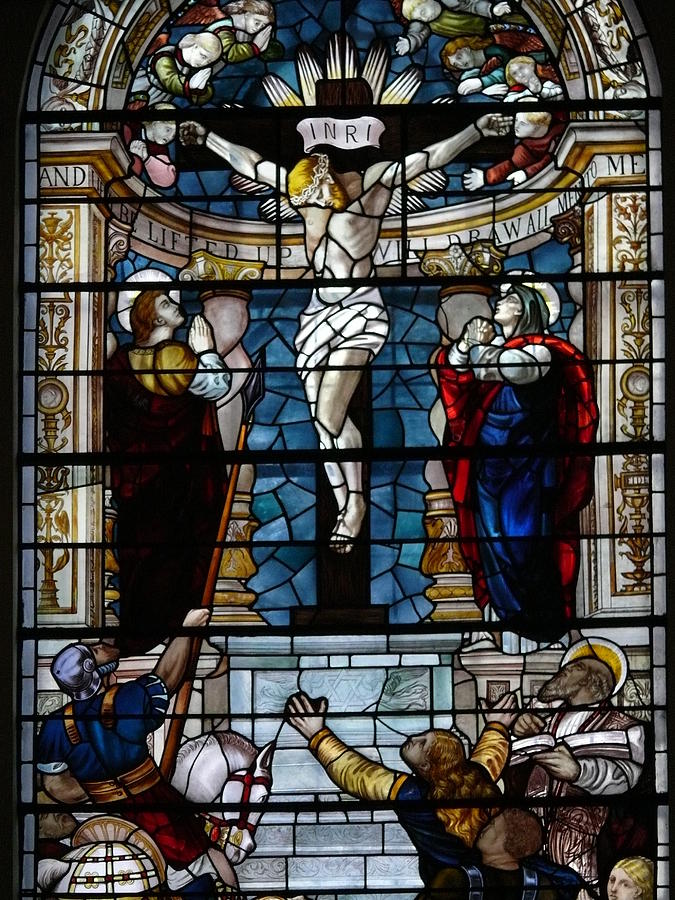

Twenty centuries ago, the world was saved through the torture and murder of an innocent man. This frankly uncomfortable truth lies at the heart of any honest Christian witness to our community and world. We can spend all day talking about how great Christianity is for one’s family or how Christianity transforms lives, disrupts addictions, and brings real peace in a compromised and chaotic world, but these good effects are utterly meaningless without the uneasy reality our liturgy forces us to march through every Holy Week. These good effects, can in fact, become idols in an inwardly turned religion which fails to place the dying Son of God at the heart of its understanding of the universe. There is no Christianity without the cross and passion; no hope without the blood and sweat and betrayal and death of Christ. The four Gospel writers make the cross the center of their theological histories because the cross is the center of all creation—the moment in time when God and Man most honestly showed who they really are.

It is for this reason that we, following the tradition of the evangelists themselves, focus so much this week on the death of Christ on the cross for our redemption. We will never be exposed to a more honest picture of the human condition than the darkened hours God spent nailed to a tree. On that day, the greatest religion in the world and the most powerful political state ever conceived came together to stand before the Prince of Peace and torture him to death. It is this pivotal moment, when our best came into contact with God’s best that both the true ugliness of humanity and the unsearchable love of God came into full focus forever. It is no wonder so many people, including Christians, hide from the cross. We hide because the cross reveals who we truly are in the story of the world: we are the confused and the lost; we are the betrayers and the murderers; we are the unnatural enemies of the God who is love. The cross forces us to confront this truth, and for good reason, we don’t like it.

I was meditating this week on this stark reality—most perfectly displayed on Calvary’s dark hill—as news reports came in from Bucha, the suburb of Kiev where hundreds of civilians have been discovered in mass graves. As I was reading about this old horror reanimated, I was struck by all of the ways in which the material knowledge and wealth and industry of a people can and will be used for terrible, evil ends by their leaders. The innovations necessary to create and deploy a modern army are a technological miracle born of a broken and sinful world; thousands and thousands of hours of research and work and effort must be conceived and harnessed and twisted into dutifully producing rows and rows of dead children in shallow graves. It is the exact kind of thing a world which murdered its Savior in cold blood would invent.

Some of the victims of this horror were the Sukhenko’s, a family whose mother was the mayor of their small, rural village. The Wall Street Journal had a picture of the family: husband, wife, and son bound and murdered in one of these unmarked graves. The story of those parents’ last minutes reminded me of the anguish St. Mary the Virgin must have experienced while she watched her beautiful son be executed by an occupying Roman army—utterly unable to stop the horror washing over her. On that day of days—when the earth itself shook in agony—there were only three categories of people gathered around the beating heart of the world’s future: the murderers, the cowards, and the powerless—a whole group of deformed image bearers watching the truest human die in agony. What would we say to Mary as she watched the son of promise die in the place of you and I? What would we say to the Sukhenko’s? What do we have in our hearts or minds or dreams which can possibly do anything to quench the thirst for mercy and peace and justice these parents felt down to their souls? The honest answer is that we have nothing of our own to give them. Our government is shipping in missiles and guns into Ukraine as an earnest offering to the god of “Do Something”—an action which will no doubt produce many more crying fathers and mothers—and maybe this black destruction really will mean fewer people are murdered this year—I pray it does— but I’m not here to rattle the saber or release any doves. But, if we are honest with ourselves, we know this back and forth won’t erase the horror the citizens of Bucha and Motyzhyn now know more truly than they have ever known anything.

The question for us today as we gather in this room built to remind us of God’s temple is the same question confronting everyone. Whether they are shifting uncomfortably in a pew while St. Matthew talks about evil or settling in to their favorite brunch spot or reading the New York Times while George Stephanopoulos earnestly recites from a teleprompter in the background, all these people are trying to find some way to live in a world where piles of dead children are an inescapable reminder that the false gods of modernity look an awful lot like the false gods of the past. We can run from Calvary, we can run from the cross, but we cannot run and hide from the people mocking and cheering the dying Son of God. We cannot run away from them because we are them. Any belief we have about the world and our place in it is meaningless if we cannot approach this reality; any belief we have is meaningless if we fail to honestly understand our part in the world’s evil. The only question then becomes: “Do I worship anything that overcomes or even engages the kind of evil that could produce all those lifeless eyes staring back at me?” If the answer we give is brunch or an extra hour of sleep or money or missiles or George Stephanopoulos, then the answer is obviously, “No.”

And here comes the worst part: the moment when we are tempted to shrug our shoulders and say, “Well, what can you do?” and move on to the next thing. There is an honesty to this exclamation of powerlessness which has much to commend it—at least we aren’t pretending we have some kind of magic spell or perfectly comforting phrase or new technology able to banish the great pain sin and death cause in our world. “But, what can you do?” Well, if you are the Son of God made Man, you climb onto a cross and save the damned world: you allow the creatures you created to beat you and nail you to a wooden beam. Why? Because, in the face of pure evil, God reveals His righteousness by sharing our suffering and pain. There is no airbrushing or meaningless platitudes here, only God taking our worst and giving us His love in return: an endless, unsearchable love which proves forever that suffering and pain are not only honored by God but that suffering and pain are victory in a world which murders and destroys children to increase its temporary wealth or comfort or power. God the Father takes the suffering and pain of God the Son and redirects Mankind’s evil and hate to defeat death in a way we can never claim was our idea. We didn’t die on the cross; we would never even think of saving anyone this way, except of course, if we asked Olha Sukhenko what she would do to save her murdered son. In that moment of brutal honesty born of suffering and pain, she would scream to us, “Take me, take me,” and my God she would mean it. God means it too, and that is why He died for us.

As the Prophet Isaiah tells us, seven hundred years before Christ suffered in our place:

And he will destroy in this mountain the face of the covering cast over all people, and the vail that is spread over all nations. He will swallow up death in victory;

and the Lord God will wipe away tears from off all faces; and the rebuke of his people shall he take away from off all the earth: for the Lord hath spoken it. And it shall be said in that day, Lo, this is our God; we have waited for him, and he will save us: this is the Lord; we have waited for him, we will be glad and rejoice in his salvation (Isaiah 25:7-9).

When we look at the cross we see God’s strange and unnerving power; a power we quite simply don’t understand. We see a bleeding man on a cross, a grieving mother in the dirt, and a legion of men warped by evil mocking their suffering king. Jesus tells us this cross is what victory looks like, and we can’t help but shake our heads. We say in our words and lives, “Oh, God you can’t be serious. This dying, broken man, this can’t be how the world is saved. No God is that powerful.” It is the same harrowing doubt we feel when we look at those dead Ukrainian children. We say in our fear and dread, “There is no God who can redirect this madness and evil and hatred for his saving purposes. No God is that powerful.” We even say in our pride and vanity, “God can’t save me in my sinfulness. No God is that powerful.” But, the cross always says, “Yes.” Yes, Calvary is the hill upon which the City of God will be built with wood and nails and tears and blood. Yes, Calvary is the hill where God declared His everlasting union with the broken and the hurt and the lost. Yes, Calvary is the hill where you and I were saved. In His weakness is more strength than we can even imagine. It is this strength which makes the cross the world’s “Yes,” the empty tomb our future, and death a conquered foe. Let us, therefore, lift high the cross, stare even the worst suffering in the eyes, and know the glory of God marches undeterred in the valley of death and the dark mountain of despair.