Now these things happened to them as an example, but they were written down for our instruction, on whom the end of the ages has come (1 Corinthians 10:11).

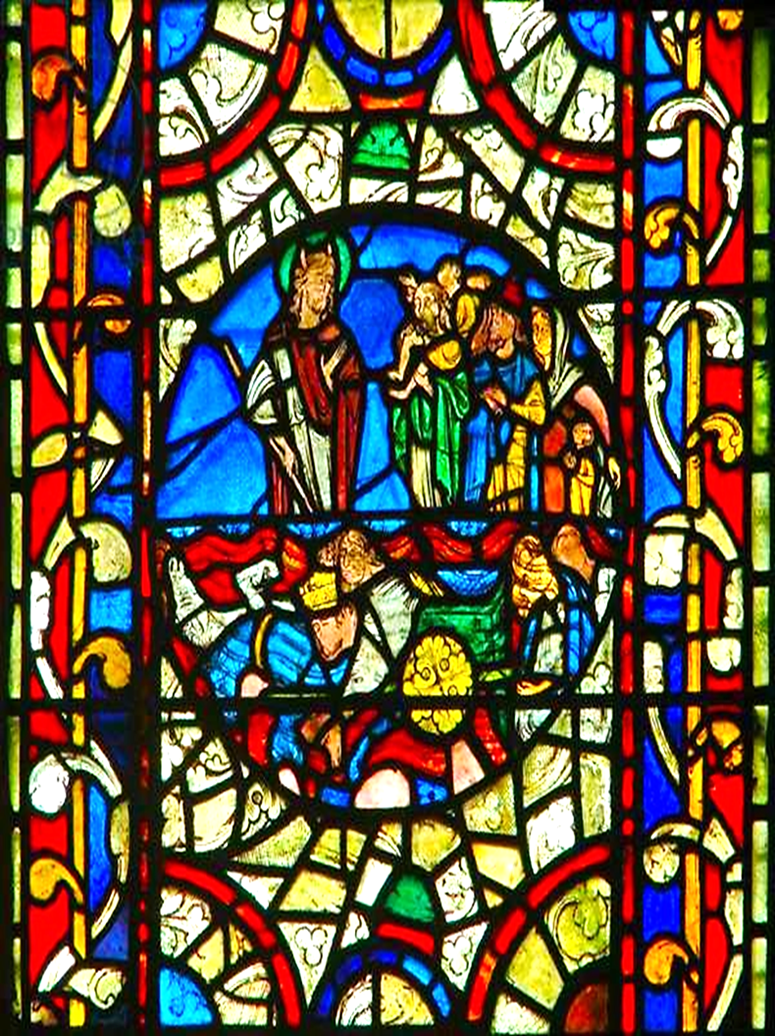

There is a moment in the beginning of today’s epistle from St. Paul where the martyred apostle embraces us as the family for which he was willing to die. He says, ‘Brethren…all our fathers were under the cloud’ (1 Cor. 10:1). We should pause for just a moment and realize what the apostle was saying to these 1st century former Gentiles, and to us for that matter; he was reminding them of the change in their very history which occurred at their baptism and welcome into the people of God. This transformation of their lives through the power of the Holy Ghost reaches back through their family history and gives them new ancestors and a new story from which they are to draw their identity. Becoming the people of God means a new future—spent in the new heaven and new earth—but it also means a radically different past, for the history of Abraham and Isaac, Ruth and David, Christ and Paul, this historic struggle between human sinfulness and the God who won’t let our weakness murder creation, that story becomes our story and every other story becomes as alien to us as the history of some other family unrelated to us by law or blood.

Do we think of the Old and New Testament as our family history? St. Paul, as a matter of life and death, commands us to do just that, but in my experience, people usually know vastly more about the history of their favorite distractions than they do about the family and kingdom God has been forming from the beginning of time. This intentional unknowing is a tragic circumstance of even the modern, busy, over stimulated Christian because it transforms the Christian faith into a series of cold and abstract ideas rather than the living, breathing continuance of a family brought together by God to walk through the wilderness of a fallen world. One can try to be a Christian without embracing this new family and its history, but this self-orphaning will inevitably lead to some other family and history taking its place, and every other family and history is dying.

It is just this kind of misplaced family allegiance which forces Paul to invoke the history of God’s people to head off disaster in Corinth. The context for today’s theological history lesson can be found in the Corinthian church’s attitude toward joining with their pagan neighbors in idolatrous feasts. In the ancient world, the various religions would sacrifice animals to the gods and then crowds would feast on the remains. These events were religious but also important social gatherings which had significant meaning for the Gentiles and their civic culture. To abstain from such feasts carried a heavy social cost and marked one as an outsider. St. Paul understands this problem and advises the Corinthians by saying, in effect, ‘Does your Christianity make you an outsider? Good, you are an outsider who has no business engaging in the substitute liturgies of a dying world—they are not your family, and this isn’t your history.’

And, frankly, who would want that history when it is compared to the beautiful summary of God’s providential care offered by St. Paul today. He writes, ‘…our fathers were under the cloud, and all passed through the sea; And were all baptized unto Moses in the cloud and in the sea; And did all eat the same spiritual meat; And did all drink the same spiritual drink: for they drank of that spiritual Rock that followed them: and that Rock was Christ’ (1 Cor. 10:1-4). To be a baptized Christian who partakes in the spiritual meat and spiritual drink of Christ is to be part of God’s chosen people on earth; it is to be connected through time and space to the saving work of the Trinity that began as soon as humanity first put the knife to our own throat and screamed at God ‘You can’t tell me what to do!’ The most important moment in that story, before the coming of Christ, was the exodus of the Israelites from slavery and death in Egypt. This pivotal moment in salvation history is the dramatic first enactment of the true freedom that comes when Jesus Christ died on the cross of Calvary to break the bonds of sin and death—the day He died wrestling the knife out of our hands. On that day, our slavery to all the gods of this world was broken in a way we see foreshadowed in the liberation of God’s people through the defeat of Egypt’s gods in the first exodus. Just as God used plagues which represented the gods of Egypt to mock their powerlessness, God the Son submitted to evil’s most terrible weapon—death—to reveal Evil’s utter powerlessness in comparison to the love of God. Christ’s public resurrection and empty tomb are the great declarations of freedom for a humanity held captive by our fear of death and loss. The result of this titanic Trinitarian effort was the liberation of all those who trust that Christ will provide everything we need to make it through our own wilderness wanderings. Our vindicated Savior has set us free to love and live without the chains of sin and death dragging us back to the slave camp.

Unfortunately, some the Corinthian Christians had come to the perverse conclusion that their freedom in Christ, their freedom as children of God, meant that they could engage in idolatry and suffer no ill effects. And make no mistake, every sin St. Paul lists today has idolatry at its heart. Idolatry, of course, can involve the use of idols, like the Golden Calf, but it has a much broader definition as the worship of created things rather than the Creator. The Corinthian Christians may not have been bowing down before the idols of the Gentiles, but they were misusing their Christian freedom to feast and commit sexual immorality in the name of the gods to whom they were formally enslaved. We would well remember that the false gods of our age aren’t called Baal or Moloch or Ashtaroth, but hold much more pleasing names like power, greed, and sex—the worship of these gods is celebrated in almost all quarters of our wounded society.

Grasping this broader understanding of idolatry helps us to understand why St. Paul, the champion of freedom in Christ, insists that the people of God live their everyday lives in worship to the true God. As he tells the first Roman Christians, ‘I beseech you therefore, brethren, by the mercies of God, that ye present your bodies a living sacrifice, holy, acceptable unto God, which is your reasonable service. And be not conformed to this world: but be ye transformed by the renewing of your mind, that ye may prove what is that good, and acceptable, and perfect, will of God’ (Romans 12:1-2). St. Paul is showing us that the worship we conduct in this building is designed to strengthen us for the worship we offer to the Lord in our everyday lives of loving obedience and faithfulness. To be a follower of Christ, we must purge our minds of the toxic brainwashing of our culture and embrace the sacrificial love most perfectly shown on the cross and in the 33 years God the Son lived through the daily humiliations of being human in a fallen world. The way we most perfectly follow Christ is to live our lives as a worshipful sacrifice to the Father. That means we do not just worship for an hour on Sunday; no, it means we are always worshipfully sacrificing. When we awake in the morning, until we lay down to sleep, every activity—at our work or in our leisure—needs to be considered a part of our necessary worship of the God who hasn’t just saved us for an hour on Sunday but has saved us for every minute of every day.

The early church, and the historic Anglican Way, gathered daily to remind themselves of this calling and to steel themselves against the hostile idolatry of the wounded world; they gathered together to prepare themselves to walk out into a fallen land and worship their Savior with every step and breath. They knew that we are always worshipping something—the only real question is: What are we worshipping? We cannot look to the world for our example of the Christian life: a world in which we are told it is fine to worship God in our churches, but then we must put aside our religion; our true family; our destiny; our hope—we must put all that aside—in order to fit into a world committing suicide before our eyes. St. Paul is bellowing at us from the pages of His epistle: ‘No. Stop. Understand who you are and where you are!’ We are not in the promised land surrounded by good people on their way to heaven; no, we are wandering in a desert that will be littered with the corpses of all those who spit in the eye of the God who has moved heaven and earth to save us. We are either running through this present desert, hoping our own cleverness or strength or beauty will save us, or we are faithfully clinging to the Rock from which living water flows.

Gloriously, when we do recognize our place in created time, when we do look about the desert of our fallen world and seek everlasting sustenance in the God who is faithful, then we can finally see we are living in the blessed age of fulfillment. Christ has won the victory, the Holy Spirit has broken loose our chains, and we are marching toward the Jerusalem not made with hands. Our fulfillment in this life comes only from our progress toward this goal—our progress toward the resurrected earth which awaits the children of God at the end of their journey. Just as Moses called the Israelites to be a nation of priests, we have been called to be a royal priesthood, a holy nation, a peculiar people who every second show forth the praises of Him who has called us out of darkness into marvelous light. We are to walk from room to room in this darkened land and bless it with the presence of the Holy Spirit and a dead human made alive by His power. May we dead men and women made alive always know our history and our destiny, and may we worship our God and Savior with every hour we have breath.