Pure religion and undefiled before God and the Father is this, To visit the fatherless and widows in their affliction, and to keep himself unspotted from the world. (James 1:27).

In today’s Gospel reading, our Lord tells the apostles, just hours before his betrayal and death, “…be of good cheer; I have overcome the world.” The appropriate response to this declaration was certainly to laugh or maybe cry. Here was the apostles’ master claiming to have overcome the world as he huddled with His out of work fishermen and traitorous tax collector in a little upstairs room. Tiberius Caesar ruled the Roman Empire from a golden palace, the Sanhedrin called the Temple of God their meeting hall, but Jesus dared to say that he had overcome them all with His table and His bread and His wine. If any of us had been sitting at that table, would we have agreed with Him?

This claim seems even more ridiculous when Jesus’ own countrymen hand Him over to be crucified by the occupying Roman Army. By the standards of the world, by the metric the world has always used to measure power and victory, the humiliation and death of Christ appears to be the greatest reason to dismiss Him as a tragic figure at best, a loser or fool at the worst. This dismissal is exactly how our fallen world treats its Messiah. Maybe not in so many words, but living one’s life as if nothing happened in AD 33 is the same as accepting the final verdict of Christ’s assassins. In our own community, it is usually stated in terms of practicality. People, say, ‘I’m a Christian, but it’s impractical to believe or do x,’ x being whatever the person doesn’t want to do. This position is a perfectly reasonable one to take if the death of Christ was the end of Jesus’ ministry—if the Pharisees and Sadducees were right and Jesus was simply a misguided or blasphemous interloper who had to be murdered to keep the peace. We are taught to ever so solemnly move Jesus into the same category as Martin Luther King Jr. or Gandhi or Thomas Jefferson: complicated men who had world-changing ideas, but we certainly don’t have to believe everything they said. Dead men can’t tell us what to do, and so we don’t let them.

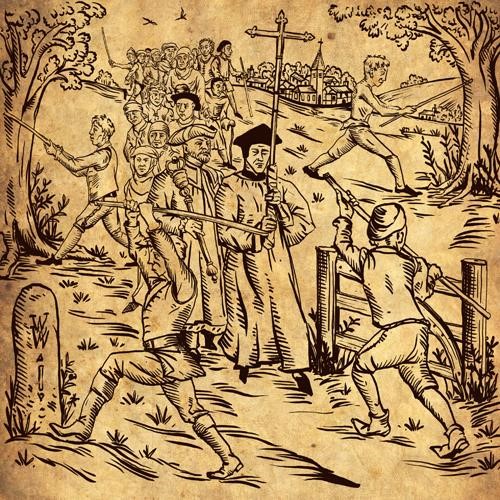

Don’t get me wrong, we are all haunted by the ideas of dead men and women. Their ghostly influence holds sway over so much of what we deem to be our own unique identities, but we can always say, ‘No,’ to a ghost. Which makes what actually happened in AD 33 all the more amazing. These apostles, these confused and scared men gathered around the Lord’s table, will soon be the most intimate witnesses to God the Son’s humiliation and exaltation through His death and bodily resurrection, and at the end of this emotional and spiritual roller-coaster these men will hear this from He who overcame the world, ‘…All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me. Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, teaching them to observe all that I have commanded you. And behold, I am with you always, to the end of the age’ (Matthew 28:18). We too often hear these words, as if they were the confident boastings of the first string quarterback yelled into a bullhorn before we play our cross town rivals, rather than what they really are. Jesus is issuing a suicide mission for these men; he is making them outcasts from their own people and outlaws in the most powerful empire the world had ever seen. All of them will die in the gruesomest ways their persecutors’ evil imaginations can devise, but they will never waver from the commands of the Man whose renewed life demanded their deaths. The resurrected Christ, the living, breathing evidence of life after death, demands nothing less.

The Great Commission then, the creation of the Christian religion by its resurrected King, has nothing to do with some Disney world version of Christianity we have been sold for far too long—cute, nice, dead. As we prepare, God willing, for future baptisms here at Trinity, I am reminded that far from being a sweet opportunity for pictures and cake, the baptismal rite the risen Christ established that day is a declaration of war against evil. It is the drafting of another human soul into the fight against sin, the flesh, and the devil, and when his parents, Godparents and the congregation as a whole swear to raise a child in the faith—we are saying, ‘Let my death and the death of this child be the ultimate proclamation of Christ’s resurrected life to the world; let the old way to be human die in that water, and let us live together as the resurrected ones.’ We are either signing up for that fight and that death, or we are acting out some kind of empty, useless rite of passage—no more important than our 16th birthday party or the local gender reveal balloon release. The church can only be the church when we are serving as a dying witness whose death points to the reality that lies beyond death. This calling was the terrible responsibility laid on the shoulders of the apostles, and it is the same responsibility we have today as the apostolic church they midwifed into existence.

Our religion then is the living out of that triumphant daily dying in our lives. We need only look to the example the Apostle James provides for us today. He writes, ‘Religion that is pure and undefiled before God the Father is this: to visit orphans and widows in their affliction, and to keep oneself unstained from the world’ (James 1:27). Is this how we would describe the Christian religion? One of the most depressing things about being a priest is the conversations I have with people who are church shopping—a term I loathe. The people who come for one service and never return are always the people who give me a laundry list of things that would need to change before they would ever come back, as if I’m some sort of short order cook at a restaurant: less talk about sin, more entertainment, no mayonnaise and extra pickles, etc. Honestly, what I want to say back is, ‘Go to Hell,’ but that would most certainly be the un-Christian thing to do. What I must say, however, is, ‘No.’ I have to say, ‘No,’ because I know how hard a thing we are being commanded to do by St. James today in the name of his Lord and Savior, and if we approach this command as consumers rather than the utterly dependent children of God, we will die and drag others down with us.

James tells us to care for orphans and widows as they are going through their “affliction” or tribulation; in fact, the Greek word is the same as the ‘tribulation’ Jesus tells His apostles they will soon meet—the tribulation all true Christians face as they rebel against the Prince of Darkness and the mad world he has stained with the excrement of his lies. Orphans and widows are James’ examples because orphans and widows have always been chosen as the special recipients of God’s love and mercy in our fallen world. There are many examples of this phenomenon, but here are two from the Psalms, ‘[God] is a Father of the fatherless, and defendeth the cause of the widows; even God in his holy habitation’ (Psalm 68:5); ‘[God] will defend the afflicted among the people and save the children of the needy; he will crush the oppressor’ (Psalm 72:4). In the New Testament, these afflicted people are those Jesus has already said are blessed in the Beatitudes; these are the people St. Mary the Virgin has thanked God for protecting in her Magnificat. It is those who are especially oppressed and mistreated by this fallen, evil world that God’s people must be ready to die for, for they are the living opportunities to combat evil with the love of God.

Further, as if that wasn’t enough, our protection of those most afflicted by evil in this time of tribulation is a means by which we can keep the old man—our old sinful nature—drowning under the water of our baptism. Our sacrifice of time and money will hurt us, it will be a kind of death, but it is a sacrifice which mirrors the love of the cross because it is a sacrifice for which we can expect no repayment. It is a loving sacrifice that makes the death and resurrection of Christ concrete and visible in the eyes of the world and in the hearts of those whom we serve. In those moments of humble sacrificial love, we reveal that our love of the God who saved us now motivates us to feel the pain of sacrifice for others while simultaneously showing we belong to the new earth to come. A new earth where this divinely inspirited love will be the every second expression of our humanity. By fearlessly letting our selfishness and pride stay dead in the waters of baptism, we show that Christ’s death and resurrection are as real as the witness for which we would gladly die.

This Spirit given attitude permeates all true expressions of the Christian religion. For example, worship is not about what we get out of it, it is not about our entertainment or even our comfort, it is about witnessing to God and ourselves and our neighbors that we are willing to put our time and autonomy and selfishness to death—to put our very selves to death—in order to showcase our full fledged belief in the risen Christ and the new world His resurrection inaugurates; we show in the worship of the living God that we are willing to execute all the parts of our nature the world tells us make us gods. To sacrifice this false deity is to reveal a trust which moves the hearts of men and banishes the demons of our age. Every moment we can carve out of our existence to make this fact known is a moment in which we have bound ourselves to the victory of the cross; it is a moment we have made the empty tomb our assured destiny.

And so, we stay unstained from this evil world by living the new life we began at our baptisms. I do not care how dirty you think you’ve gotten since the day you were washed in the blood of the Lamb; it is never too late to fall on our knees before God’s holy table and stand to fight and die for the world He came to save. That is the Christian religion, and it is the faith worth dying for.