But the Scripture imprisoned everything under sin, so that the promise by faith in Jesus Christ might be given to those who believe (Galatians 3:22).

Both today’s Epistle and Gospel readings are concerned with the great question of human existence, “How can I be saved?” The religious lawyer who approaches Jesus asks this very question, “Master, what shall I do to inherit eternal life?” (St. Luke 10:25). It’s a good question, asked here for the wrong reasons, but nonetheless, it is truly fascinating how rarely the question of eternal salvation overtly pops up in our modern discourse—polite or otherwise. I talk with people all the time, wearing a Christian uniform all day, and no one ever asks me this question. The conversations are always about fixing some part of the person’s life which isn’t going according to our culture’s plan, or the conversation is an opportunity for the person to brag about how religious or spiritual they are (much like today’s lawyer). It is a rare encounter indeed where someone talks frankly to me about how desperately fallen they are and how much they need a Savior. Humanity has an incredibly powerful entitlement mentality which blocks us from seeing both our own sinfulness and our tragic inability to save ourselves. We think we deserve salvation because, when compared to other people, we’ve done more “right” things than them. We hear “…love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your strength and with all your mind, and your neighbor as yourself,” and say—along with the lawyer—“I think I’m pretty close to this command, but what do you mean by neighbor?” We think or say this lawyerly idea; rather, than answering Jesus with the only reasonable and logical response: “Against thee only have I sinned, and done this evil in thy sight; that thou mightest be justified in thy saying, and clear when thou shalt judge. Behold, I was shapen in wickedness, and in sin hath my mother conceived me.” (Psalm 51:4-5).

When we mistakenly think we have any standing to engage in a negotiation with the God of Wrath and Life, we become like the priest and the levite passing by our dying brother today, clinging to our self-righteousness as if it were any protection against the death which too haunts our existence. If we are dying, and I can assure you we all are, than the path to life can only be found in a life which expresses the love which can actually defeat death, the love which carries adversity and suffering through the grave and into the new heaven and new earth. The grim tale of human history should reveal plainly enough that this love will not flow from the imagination or will of men; it isn’t a love which can be forced out of us with gulags or motivational speeches; it must be a gift from the God who created love, and St. Paul tells us today how this God will make a love capable of saving all dying men. Indeed, a love capable of saving even priests and levites.

What really binds today’s two readings together is this shared idea of “inheritance.” What does it mean to “inherit eternal life?” Does one earn this great inheritance through our own righteous actions, or are we the recipients of an inheritance whose author and finisher is God alone? Man’s entire fallen inclination is to believe our so-called righteous actions are what save us, and this mistaken understanding of who we are leads to the violence and despair and selfishness which rages in the hearts of men. As an example, there exists in our country today an epidemic of what are now being called “Deaths of Despair.” This term refers to deaths involving drugs, suicide, and alcohol. The Center for Disease Control has this harrowing set of statistics: “Between 2007 and 2017, among adults ages 18-34, drug-related deaths increased by 108%, alcohol-related deaths increased by 69% and suicides increased by 35%.” In 2017 alone, 36,000 millennials died “deaths of despair,” and as we sift through the wreckage of 2020, we can be sure to see an elevated version of those numbers. There is an intense irony visible in a society placing armed guards in schools to protect children from nihilistic young men while we do precious little to reform a culture and its institutions which churn out generations of young people who are murdering themselves at the death rate of a Vietnam War every two years. All this has happened, by the way, amidst the longest period of economic growth in the history of the world—surrounded by an unparalleled age of technology, entertainment, and sexual possibilities. Add to these grim figures the 20,000 unborn children who are violently prevented from being born every week, and we begin to see the enormity of the campaign against the young and powerless. But, if you turn on the news or crank up social media or talk to your neighbor, manifestly few people are talking about this existential crisis. Why? Well, because there is no way to combat this holocaust and be the captains of our own self-indulgent, personal salvation campaign; there is no way to fight evil on this scale and be worried about attaining the marks of modern righteousness. We can’t prevent people from hurting themselves unless we are prepared to die for them, and we won’t ever be able to die for others if we don’t fully trust that God has died for us; if we don’t faithfully trust that God keeps His promises even if it means using His own body to smother the grenade of our selfishness.

Here is why St. Paul is dragging us away from a reliance upon our perceived performance of the law back to the foundational covenant made between God and humanity’s representative: Abraham. God promised Abraham that the Trinity would save our broken world through the family of this old man whose very lack of sons and daughters marked him as broken and worthless. Abraham’s Creator, our Creator, made an unbreakable promise to His unworthy, ungodly, impotent creature. A creature whose only hope resided in the mercy and grace of the God whose love is most perfectly displayed on the cross we built to murder him. God cannot break His Word, and so God the Son throws Himself into the gears of pain and misery (we pretend don’t exist) to save us from ourselves—to save us from all our self-destructive attempts to make the world a better place. We haven’t begun to understand our desperate need for the grace and mercy of God until we actually confront the horror even our good intentions bring. After all, those statistics I just read are a painful indictment of a society whose purported goal is to “leave a better world for our children.” But what else can we expect from a human race whose ultimate act of self-salvation was to crucify its God on a tree? Remember, what St. John heard on the day the Lord was murdered, “The Jews answered [Pontius Pilate], “We have a law, and according to that law he ought to die…” (St. John 19:7). Doesn’t that sound reasonable? “It’s out of our hands, we’re just following the rules.” How many of us say the exact same thing, “I’m just following the rules of my culture, my society, my tribe. I can’t be expected to trust in the promises of God more than I trust in what’s expected of me.” The unfaithful Jews’ failure to trust in the promises of God led them to murder their Savior on a tree; we join with them when we trust in ourselves rather than trusting in the promises of that same God. Our trust in our work or families or accomplishments to save us puts us in the crowd of people glad to see one more trouble maker destroyed, so we can get back to the real business of saving ourselves.

And when that fails, and it always does, we are left with nothing but the gluttony or sloth or lust or materialism or “do-goodery” we were told would make us happy but eventually leaves us with nothing. We might say, “That’s not me,” but how often do we let the rules of living in the present time get in the way of living the life of love Christ reveals from the Cross? How many times are we the priest and the levite not walking to the Temple but moving from thing to thing in a desperate rush or slothful crawl to avoid the sacrificial love we know will hurt? The opioid addict is simply the master of the self-salvation game: the champion of all the religions which say I will worship whatever makes me feel the most pleasure.

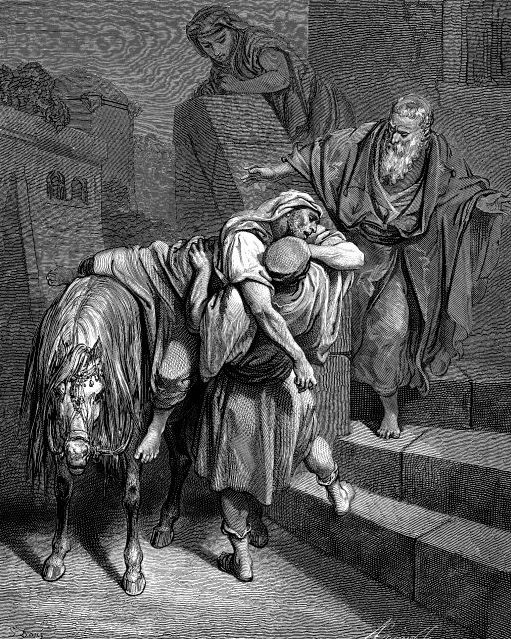

Blessedly, every part of our universe, from the greatest evils to the most pure goods, is allowed to exist because it drives all those whose eyes have been opened to see our desperate need for a Savior. St. Paul today calls the law of God a teacher and a jailer because even the holy law of God was not the end of the human story, not the end of our great redemption and becoming. The law, like pain and death and suffering, is necessary because of our selfishness and sin; they are all necessary to drive our broken hearts to seek the cure for our woundedness. When we put our lives, our confused and messed up lives, up against the standard for humanity, up against the life and love of Jesus Christ, we suddenly realize that we are not even the priest or the levite in this story: we are the naked, dying man in the gutter. We are the ones who have nothing to give except our pain and loss, nothing to give but our broken bodies and hollowed out souls. And yet, we are saved. The God of heaven and earth binds our wounds and makes us whole; He heals us with the tears and blood of His own body because it is only a love which gives unto death that can save anyone, only a love which can look at the broken bodies of the children of men and say, “Here are my sons and daughters; here is the beautiful family through which I will save the world.”

And so, let us allow the law to do its job; let us allow it and the pain and death and suffering of this world to drive us again and again to the love of the Cross—to the love which saves no matter how vile or unworthy or unlovable the recipient of that love is. It doesn’t matter if we “feel” this love in our broken souls because just like the dying man in the gutter God’s healing means of grace will save us as surely as the loving care of the Good Samaritan saved his dying enemy. We are only to get up and pray and love and study and prepare for the new world we have been saved to enjoy. That is how we will inherit eternal life, that is how we will be saved from despair, that is how we will “…go and do likewise.”