But now that you have been set free from sin and have become slaves of God, the fruit you get leads to sanctification and its end, eternal life (Romans 6:22).

Last week, our epistle reading was an answer to the question, ‘Should we keep sinning so that more and more grace can fill the earth?’ The answer, based upon the saving reality of our baptisms into Christ’s death, was an unqualified, ‘No.’ This week we are confronted with a different question, ‘If Christ has saved me, entirely outside of my performance of the law, am I now free to break the law of God, am I free to be a sinner?’ As St. Paul says, ‘God forbid.’ But, the question is not so easily answered in the minds of humanity. Let’s put this question in the singular language of our own age, ‘If I am the most happy when I am the most free from obstacles to my consumption and entertainment, why would God want to fill my life with responsibilities and obligations to love as He loves; has God made me free or has He made me a slave?’ The short, shocking answer from St. Paul is that God has made us both: the Almighty God, who is simply unconstrained by our foolish, imagined definitions of reality, has made us both freemen and slaves.

To even begin to understand what St. Paul is talking about, we must first do what seems to be an almost impossible task these days: we must get beyond the emotionally charged political meaning which terms like ‘free’ and ‘slave’ invoke. While there may certainly be found in St. Paul’s words ramifications for Christian conduct in every political age, the idea that we begin there is to betray a desire to bend the Word of God so that, twisted and mangled, it better conforms to our political ideology—the short word for this practice is slavery: slavery to weak gods who can give us nothing but want everything, slavery to men who would rob us of the truth which makes Man truly free.

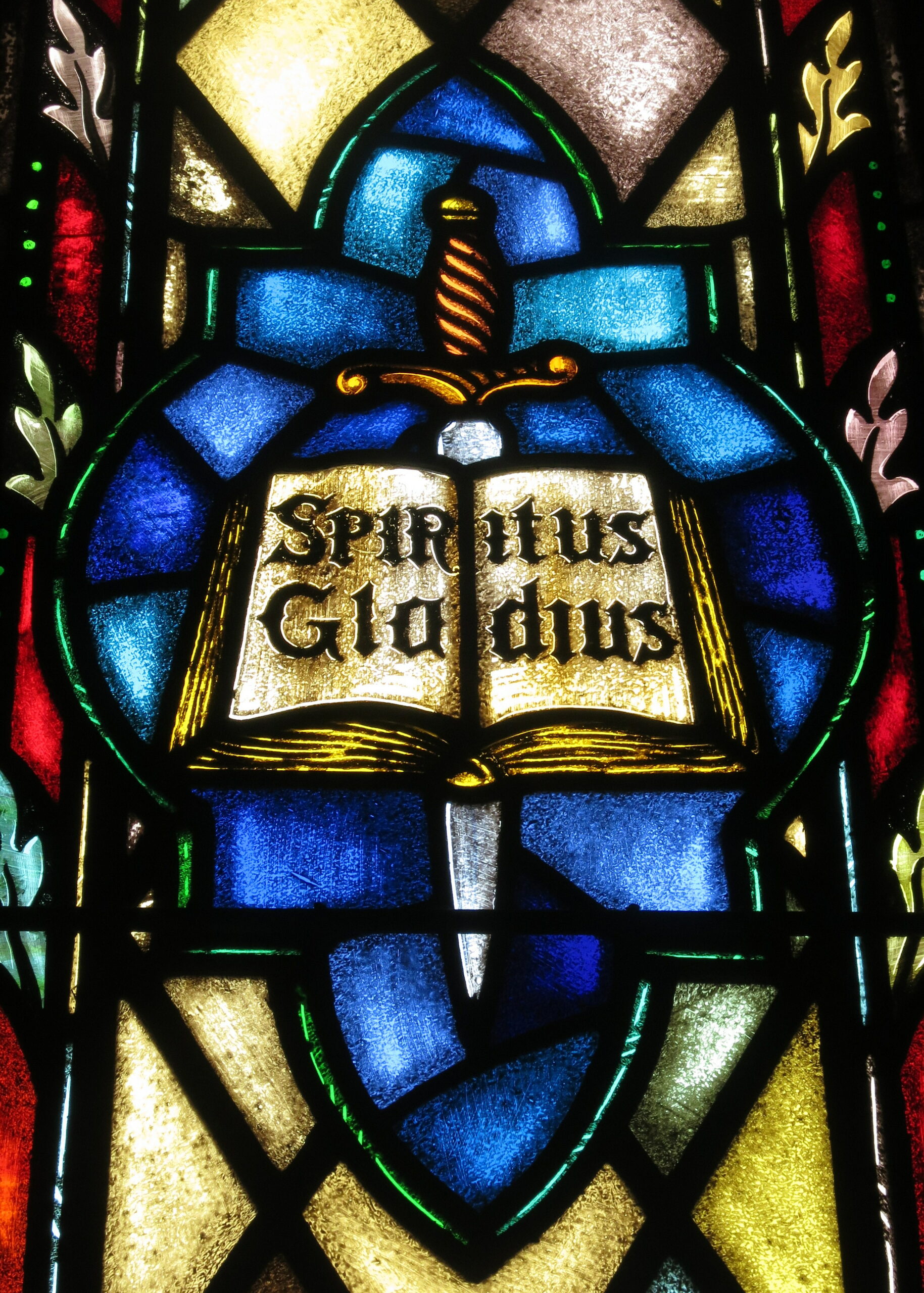

Rather than fall into the trap of trying to force the Holy Spirit revealed Scriptures to fit our experiences, or the selfish needs of our would-be slave masters, we must see that St. Paul has a specific story of liberation from slavery to which he returns again and again in his writings, namely, the Book of Exodus. The story of Israel’s liberation from the Egyptians by the mighty hand of God is vastly more important for us than any contemporary narrative of liberation because it is the story which makes it possible to know what true freedom looks like and what we need to grasp it.

Exodus tells the story of God’s public defeat of Egypt’s false gods. Before both the Israelites and the entire Gentile world, God ransacked the most powerful nation in existence through a series of plagues, each one corresponding to a different devil worshipped in their temples. For the final plague, the angel of death destroyed all the first born of Egypt sparing not even the Pharaoh’s own son—itself a brutal foretaste of the perfect judgment to come in the last days of this fallen world, a judgment which will spare no man because of his wealth or power. In Egypt, the only people spared this deserved judgment were those Israelites who faithfully spread the blood of the passover lamb on their doorposts. After this night of justice and death, the enslaved Israelites were allowed to leave. God alone had freed a people who had no army or temporal power, a people whose lives and liberty were entirely a gift from Him. In that moment, after passing through the baptismal waters of the Red Sea, to be the people of God was to be free.

But, what was it all for? Why were the Israelites freed? As we read in Exodus, ‘Then the Lord said to Moses, “Go in to Pharaoh and say to him, ‘Thus says the Lord, the God of the Hebrews, Let my people go, that they may serve me’” (Exodus 9:1). You could also translate it, ‘that they may be my slaves.’ Our outrage at such a statement is directly proportional to how highly we view ourselves, how much blind faith we have in unaided humanity, and how unaware we are of the slave masters who surround us and demand our flesh, but we are anticipating things a bit, so let’s meditate for a moment on an example of modern slavery. Several months ago, I read a story about a North Korean soldier who defected from the hermit kingdom by running through a live minefield. Upon entering South Korea, he immediately was given asylum, a place to live, and money to spend while having no family or attachments or responsibilities. He was given what many in our land would consider ultimate freedom; however, the defector was entirely unable to complete basic tasks like drive a car, order food at a restaurant, make phone calls, and on and on and on. It would have been supremely cruel to have left him alone in his ignorance, even if by educating him one inevitably curtailed his radical freedom. For the defector, freedom without knowledge was death; it was the same for the Israelites; it is the same for us.

If we think of God’s law then as the rules of true reality, we can see why God found it fitting both to free the Israelites from their slavery to Pharaoh and also why he wouldn’t then let them wander alone in the desert—-unwittingly dying of the sin disease we all carry. The tragedy of what comes next in the story (a general refusal to follow God’s law punctuated by worshipping idols and sacrificing children to devils) serves as a grim reminder of just how vast and deep this disease runs. We find it isn’t enough just to free people from their slave masters and educate them about what it means to be free; they need hearts made new and lives made holy. It is of note that the North Korean defector I mentioned earlier was eventually educated by the local government as to how to operate in a modern liberal state, but this knowledge did not prevent him from taking his own life. Freedom even with knowledge doesn’t cure sin, and sin left unhealed always leads to death.

The freedom then which St. Paul is describing today is a freedom which can only come from both knowledge of what is truly right and also the gift of a new heart by which we can follow this path of perfect freedom. As he writes, ‘But thanks be to God, that you who were once slaves of sin have become obedient from the heart to the standard of teaching to which you were committed, and, having been set free from sin, have become slaves of righteousness’ (Rom. 6:17-18). What St. Paul is telling us is that every man has a god whom he serves, or to put it another way, everyone serves some form of higher intelligence or power. The atheist who thinks himself morally and mentally superior to his Christian neighbor is simply living out the idea that whatever philosopher or politician or celebrity he borrows his beliefs from is the most intelligent, powerful being in existence. Here is one reason why these types of people tend to be so obsessed with things like extraterrestrials or multi-verses because even they know how pathetic and sad the universe would be if we are its greatest intelligence. But, we see this same kind of slavery in the self-identified Christian who knows the commands of the God who made and saved him and simply chooses to follow his fallen heart or personal experience because he thinks this is what it means to be free: this man or woman is just as much a slave to death as the atheist, just as much a slave as the Israelite dreaming about how comfortable it was back in Egypt before God freed him.

There is one question then: ‘Is the god you serve weak and impotent like Pharaoh or is the god you serve the One who defeated the Egyptian god king, the One who has, in fact, defeated death itself?’ Remember, the entire weight of the apostle’s argument rests on the historic resurrection of Jesus Christ, that event is the great public example of the Evil One’s defeat at the hands of the Living God: the second exodus for which the glory of the first was only a shadow. To be a ‘slave to righteousness’ is not to be a slave to virtue, not a slave to do-goodery or good manners; no, to be a slave to righteousness is to be a slave to the God who breathes into chaos and makes life, the God who liberates slaves and makes sons, the God who reaches into the hearts of men to burn the image of His love where no man or devil may take it. To be His new born creature is what it means to live after being saved, and it is a relation so close and intimate and unyielding in its intensity and loving obedience that the only word which Paul can use to describe it is the total allegiance of a slave to his master. To be God’s slave is to be free from sin’s life-sucking ailments for the purpose of following Christ to the death: the death of our selfishness and evil, the death of the cruel gods we allow to control us, the death of the shame which taints our every friendship and love. In its place, we have been set free to be slaves to God, to live in His world-saving purpose, to die and rise again into His new world of heavenly grace. We are to be living contradictions in a broken world where the truth will always seem like madness.

May we then be both slave and free for God and the world.